Buildings of international law: Architecture and the production of normative orders

Promotionsprojekt

Practitioners and interpreters of law are often referred to as ‘architects’, while architects themselves are rarely noticed as actors of law. In many cases, the attention of legal scholars falls on written texts, and the vocabulary of architecture is understood as a site of rhetorical and metaphorical meaning- making. Additionally, the textual focus can obscure significant spatial and material dimensions of law and its connections to authority and power, while it also prevents the investigation of different discourses, techniques and actors, such as architecture and architects, in law-making processes. While research on law and architecture has expanded beyond mere metaphor to include material readings, I argue that a further expansion of this framework is necessary to grasp the complex interplay of actors and legal spaces which constitute international law. In order to do this, I circumvent the domain of international law and architecture, focusing on the idea of architects as private actors of international law.

This project is part of the interdisciplinary Research Training Group Organising Architectures, which examines architectures as both products of and actors in collective processes, between a plethora of disciplinary actors. Understanding that social – and normative – orders cannot be separated from those of architecture, architecture’s meaning depends on complex negotiation processes. At the same time, law itself can be understood as a discursive as well as performative practice that operates in a system of multiple overlapping and interactive communities. As a result, a more nuanced notion of the nature and the function of law might form a line of inquiry that expands its scope beyond strict, literal definitions of legal concepts and frameworks.

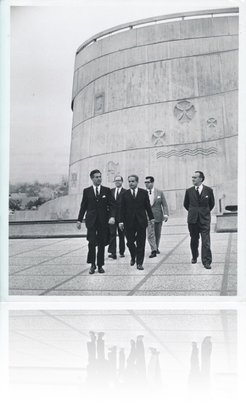

I propose a multidisciplinary engagement with law, the material spaces that embody it, and the actors involved in the making of those spaces. Toward this end, I will engage with a series of case- studies built to house international organisations through the 20th and 21st centuries, such as the headquarters of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) in Santiago, Chile; the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) in Geneva, Switzerland; and the United Nations Climate Change Secretariat, or the ‘Climate Tower’, in Bonn, Germany.

Engagement with these sites calls into questions wether physical space is capable of reflecting and commenting on the aspirations of international law, embodying, representing and translating international law’s presence and practice. Additionally, my project leads to the examination of the relation of international law’s materialisation in architecture and its discourses of authority, power and universalisation. In order to answer these questions, I will focus on the figure of the architect as a private actor, further questioning to what degree architects and architectural firms can be considered private actors of international law and how one can understand architecture in the process of translation of normative knowledge in the international context.

I will draw upon the methods and expertise of different fields such as international legal history and theory, the history of art and architecture and visual studies. Attention will fall on the negotiation processes, planning, and building of those international legal spaces in order to understand the role of architects in persuading and pushing forward styles, visual programs, and iconography that might (or might not) effectively convey international law’s principles and aspirations, as well as its political, normative, and functional goals. I argue that looking at architects while investigating international law’s history may present us with novel perspectives and methods which allow the linking of legal and the aesthetic discourses, visual and the normative programs. Additionally, when focus shifts to other actors collaborating with international law, it might be possible to better understand the discursive and disputed phenomenon of making international law both “law” and “international”.