The conversion of Japanese women to Christianity and the production of normativities: a women’s global legal history (Japan, 1540s – 1630s)

Forschungsprojekt

Portuguese traders initiated the first contact between Japan and Europe when they arrived in Tanegashima in 1543 aboard Chinese junks. Francisco Xavier, the first Jesuit in Japan, arrived in Kagoshima in 1549, where he began preaching and establishing agreements with local leaders. Later, an increasing number of missionaries went to Japan and attempted to forge alliances with daimyos and shoguns. Within a few decades, hundreds of thousands of Japanese had been baptised. Among these thousands of converted Japanese there were many women. Coming from very different social, religious and political backgrounds, these women performed different roles as Christians and influenced the practices of daily life in their communities. However, the history of these Japanese converted women and the role of women in the development and diffusion of Christianity in Japanese society remain to be properly explored.

In order to address this research lacuna, this project goes beyond the history of the few religious emissaries, their ecclesiastical politics and intellectual concerns, and contextualises the missionaries’ sources with Japanese material. While the analysis of missionaries’ letters, reports, questions on issues of daily life, pragmatic literature and histories of Japan, all of which circulated throughout the Iberian empires, plays a role, my approach also considers Japanese legal history and sources in Japanese. The aim is to write a legal history based on religious practices as normative cases, considering both traditions – not only those found in the works of the European missionaries, chroniclers and merchants, but also the normativities present in the Japanese sources, ideas, spirituality, habits and daily life, particularly women’s normative practices. Normativity, in this sense, should be understood to extend beyond the application of the legal instruments commonly attributed to the period of analysis. Religious normativities need to be included, because religion played an important role in people’s everyday life in the 16th and 17th centuries, irrespective of whether they professed Christianity or followed a specific school of Buddhism. The project seeks to employ a transnational perspective and explores how complex normative systems of different jurisdictions and traditions contributed to the emergence of practices, principles, discourses, rules and norms, particularly concerning, for instance, cohabitation practices, interfaith marriage, inheritance and kinship systems, repudiation and separation of partners, survival and network strategies. In doing so, I want to demonstrate how the role of Christian women in Japanese society redefined social positions and legal categories as they were culturally translated.

This perspective acknowledges that individual experiences of conversion varied widely among Japanese women, and that the process itself may not have followed a single, standardised path. Conversion was not a universal process, the same for every Japanese woman. By emphasising the diversity of these experiences, this project challenges assumptions and oversimplified views about conversion in the context of Japanese history, emphasising how women were ‘invisibilised’ in the historical account and in the archives, and highlighting the need to recognise and explore the richness and complexity of individual narratives within this cultural and religious context.

Located at the intersection of legal history, women’s history, gender studies and global history, my project uses local sources from different jurisdictions in archives around the world, especially the pragmatic literature produced in this period, the legal tradition adopted and adapted from China through the Ritsuryō system, the normativities from other Japanese historical periods (for example, Nara, Heian, Muromachi) and also the daimyos’ local normativities through their house code laws. Through these lenses, I will analyse how the knowledge of normativity in one specific space was able to decentralise geographical points of the Iberian empires, and overcome borders and nationalist discourses, traditional historiographical categorisation, and acritical interpretations regarding gender and sexualities, in order to write a women’s global legal history.

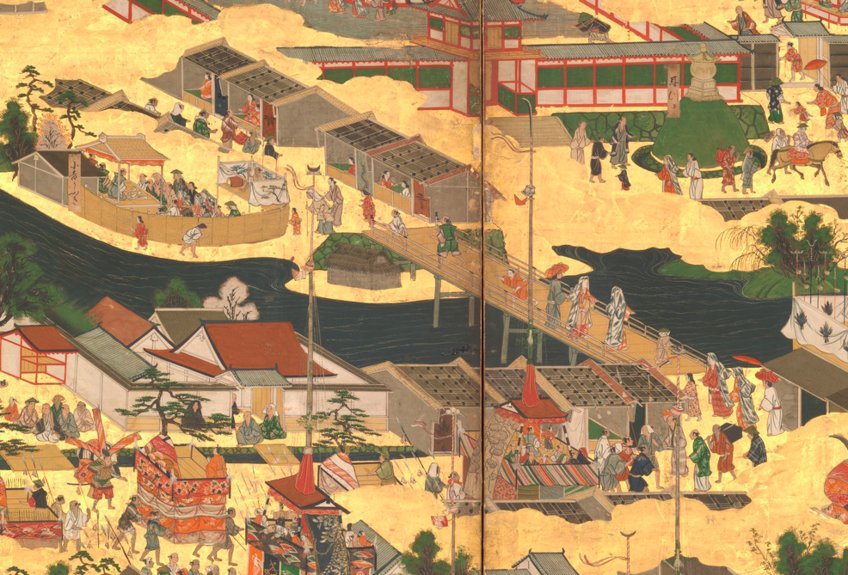

Image: Rakuchū rakugai zubyōbu - Scenes in and around the Capital, 17th century, 洛中洛外図屏風

Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015